WARNING: This documentation is not maintained anymore. Some part might be obsolete or wrong, some part might be missing but still some valuable information can be found there. Instead please refer to the ROOT Reference Guide and the ROOT Manual. If you think some information should be imported in the ROOT Reference Guide or in the ROOT Manual, please post your request to the ROOT Forum or via a Github Issue.

% Chapter: Graphics ________________________________________________________________________________________ WARNING: This documentation is not maintained anymore. Some part might be obsolete or wrong, some part might be missing but still some valuable information can be found there. Instead please refer to the ROOT Reference Guide and the ROOT Manual. If you think some information should be imported in the ROOT Reference Guide or in the ROOT Manual, please post your request to the ROOT Forum or via a Github Issue.

% Chapter: Graphics ________________________________________________________________________________________ WARNING: This documentation is not maintained anymore. Some part might be obsolete or wrong, some part might be missing but still some valuable information can be found there. Instead please refer to the ROOT Reference Guide and the ROOT Manual. If you think some information should be imported in the ROOT Reference Guide or in the ROOT Manual, please post your request to the ROOT Forum or via a Github Issue.

% Chapter: Graphics ________________________________________________________________________________________ WARNING: This documentation is not maintained anymore. Some part might be obsolete or wrong, some part might be missing but still some valuable information can be found there. Instead please refer to the ROOT Reference Guide and the ROOT Manual. If you think some information should be imported in the ROOT Reference Guide or in the ROOT Manual, please post your request to the ROOT Forum or via a Github Issue.

% Chapter: Graphics ________________________________________________________________________________________ WARNING: This documentation is not maintained anymore. Some part might be obsolete or wrong, some part might be missing but still some valuable information can be found there. Instead please refer to the ROOT Reference Guide and the ROOT Manual. If you think some information should be imported in the ROOT Reference Guide or in the ROOT Manual, please post your request to the ROOT Forum or via a Github Issue.

% Chapter: Graphics ________________________________________________________________________________________ WARNING: This documentation is not maintained anymore. Some part might be obsolete or wrong, some part might be missing but still some valuable information can be found there. Instead please refer to the ROOT Reference Guide and the ROOT Manual. If you think some information should be imported in the ROOT Reference Guide or in the ROOT Manual, please post your request to the ROOT Forum or via a Github Issue.

Graphical capabilities of ROOT range from 2D objects (lines, polygons, arrows) to various plots, histograms, and 3D graphical objects. In this chapter, we are going to focus on principals of graphics and 2D objects. Plots and histograms are discussed in a chapter of their own.

In ROOT, most objects derive from a base class TObject. This class has a virtual method Draw() so all objects are supposed to be able to be “drawn”. The basic whiteboard on which an object is drawn is called a canvas (defined by the class TCanvas). If several canvases are defined, there is only one active at a time. One draws an object in the active canvas by using the statement:

This instructs the object “object” to draw itself. If no canvas is opened, a default one (named “c1”) is instantiated and is drawn.

root[] TLine a(0.1,0.1,0.6,0.6)

root[] a.Draw()

<TCanvas::MakeDefCanvas>: created default TCanvas with name c1The first statement defines a line and the second one draws it. A default canvas is drawn since there was no opened one.

When an object is drawn, one can interact with it. For example, the line drawn in the previous paragraph may be moved or transformed. One very important characteristic of ROOT is that transforming an object on the screen will also transform it in memory. One actually interacts with the real object, not with a copy of it on the screen. You can try for instance to look at the starting X coordinate of the line:

X1 is the x value of the starting coordinate given in the definition above. Now move it interactively by clicking with the left mouse button in the line’s middle and try to do again:

You do not obtain the same result as before, the coordinates of ‘a’ have changed. As said, interacting with an object on the screen changes the object in memory.

Changing the graphic objects attributes can be done with the GUI or programmatically. First, let’s see how it is done in the GUI.

As was just seen moving or resizing an object is done with the left mouse button. The cursor changes its shape to indicate what may be done:

Point the object or one part of it:

Rotate:

Resize (exists also for the other directions):

Enlarge (used for text):

Move:

Here are some examples of:

Moving:  Resizing:

Resizing:

Rotating:

How would one move an object in a script? Since there is a tight correspondence between what is seen on the screen and the object in memory, changing the object changes it on the screen. For example, try to do:

This should change one of the coordinates of our line, but nothing happens on the screen. Why is that? In short, the canvas is not updated with each change for performance reasons. See “Updating the Pad”.

Objects in a canvas, as well as in a pad, are stacked on top of each other in the order they were drawn. Some objects may become “active” objects, which mean they are reordered to be on top of the others. To interactively make an object “active”, you can use the middle mouse button. In case of canvases or pads, the border becomes highlighted when it is active.

Frequently we want to draw in different canvases or pads. By default, the objects are drawn in the active canvas. To activate a canvas you can use the TPad::cd() method.

The context menus are a way to interactively call certain methods of an object. When designing a class, the programmer can add methods to the context menu of the object by making minor changes to the header file.

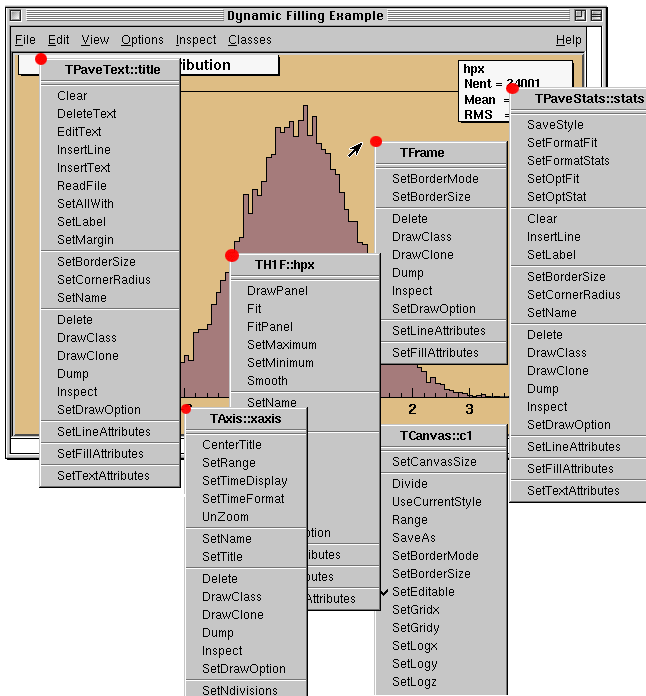

On a ROOT canvas, you can right-click on any object and see the context menu for it. The script hsimple.C draws a histogram. The image below shows the context menus for some of the objects on the canvas. Next picture shows that drawing a simple histogram involves as many as seven objects. When selecting a method from the context menu and that method has options, the user will be asked for numerical values or strings to fill in the option. For example, TAxis::SetTitle will prompt you for a string to use for the axis title.

The curious reader will have noticed that each entry in the context menu corresponds to a method of the class. Look for example to the menu named TAxis::xaxis. xaxis is the name of the object and TAxis the name of its class. If we look at the list of TAxis methods, for example in https://root.cern/doc/master/classTAxis.html, we see the methods SetTimeDisplay() andUnZoom(), which appear also in the context menu.

There are several divisions in the context menu, separated by lines. The top division is a list of the class methods; the second division is a list of the parent class methods. The subsequent divisions are the methods other parent classes in case of multiple inheritance. For example, see the TPaveText::title context menu. A TPaveText inherits from TAttLine, which has the method SetLineAttributes().

For a method to appear in the context menu of the object it has to be marked by // *MENU* in the header file. Below is the line from TAttLine.h that adds the SetLineAttribute method to the context menu.

Nothing else is needed, since Cling knows the classes and their methods. It takes advantage of that to create the context menu on the fly when the object is clicking on. If you click on an axis, ROOT will ask the interpreter what are the methods of the TAxis and which ones are set for being displayed in a context menu.

Now, how does the interpreter know this? Remember, when you build a class that you want to use in the ROOT environment, you use rootcling that builds the so-called stub functions and the dictionary. These functions and the dictionary contain the knowledge of the used classes. To do this, rootcling parses all the header files. ROOT has defined some special syntax to inform Cling of certain things, this is done in the comments so that the code still compiles with a C++ compiler.

For example, you have a class with a Draw() method, which will display itself. You would like a context menu to appear when on clicks on the image of an object of this class. The recipe is the following:

The class has to contain the ClassDef/ClassImp macros

For each method you want to appear in the context menu, put a comment after the declaration containing *MENU* or *TOGGLE* depending on the behavior you expect. One usually uses Set methods (setters). The *TOGGLE* comment is used to toggle a boolean data field. In that case, it is safe to call the data field fMyBool where MyBool is the name of the setter SetMyBool. Replace MyBool with your own boolean variable.

You can specify arguments and the data members in which to store the arguments.

For example:

class MyClass : public TObject {

private:

int fV1; // first variable

double fV2; // second variable

public:

int GetV1() {return fV1;}

double GetV2() {return fV2;}

void SetV1(int x1) { fV1 = x1;} // *MENU*

void SetV2(double d2) { fV2 = d2;} // *MENU*

void SetBoth(int x1, double d2) {fV1 = x1; fV2 = d2;}

ClassDef (MyClass,1)

}To specify arguments:

This statement is in the comment field, after the *MENU*. If there is more than one argument, these arguments are separated by commas, where fX1 and fY2 are data fields in the same class.

If the arguments statement is present, the option dialog displayed when selecting SetXXX field will show the values of variables. We indicate to the system which argument corresponds to which data member of the class.

This paragraph is for class designers. When a class is designed, it is often desirable to include drawing methods for it. We will have a more extensive discussion about this, but drawing an object in a canvas or a pad consists in “attaching” the object to that pad. When one uses object.Draw(), the object is NOT painted at this moment. It is only attached to the active pad or canvas.

Another method should be provided for the object to be painted, the Paint() method. This is all explained in the next paragraph. As well as Draw() and Paint(), other methods may be provided by the designer of the class. When the mouse is moved or a button pressed/released, the TCanvas function named HandleInput() scans the list of objects in all it’s pads and for each object calls some standard methods to make the object react to the event (mouse movement, click or whatever).

The second one is DistancetoPrimitive(px,py). This function computes a “distance” to an object from the mouse position at the pixel position (px, py, see definition at the end of this paragraph) and returns this distance in pixel units. The selected object will be the one with the shortest computed distance. To see how this works, select the “Event Status” item in the canvas “Options” menu. ROOT will display one status line showing the picked object. If the picked object is, for example, a histogram, the status line indicates the name of the histogram, the position x,y in histogram coordinates, the channel number and the channel content.

It is nice for the canvas to know what the closest object from the mouse is, but it’s even nicer to be able to make this object react. The third standard method to be provided is ExecuteEvent(). This method actually does the event reaction. Its prototype is where px and py are the coordinates at which the event occurred, except if the event is a key press, in which case px contains the key code.

Where event is the event that occurs and is one of the following (defined in Buttons.h):

kNoEvent, kButton1Down, kButton2Down,

kButton3Down, kKeyDown, kButton1Up,

kButton2Up, kButton3Up, kButton1Motion,

kButton2Motion, kButton3Motion, kKeyPress,

kButton1Locate, kButton2Locate, kButton3Locate,

kKeyUp, kButton1Double, kButton2Double,

kButton3Double, kMouseMotion, kMouseEnter,

kMouseLeaveWe hope the names are self-explanatory.

Designing an ExecuteEvent method is not very easy, except if one wants very basic treatment. We will not go into that and let the reader refer to the sources of classes like TLine or TBox. Go and look at their ExecuteEvent method! We can nevertheless give some reference to the various actions that may be performed. For example, one often wants to change the shape of the cursor when passing on top of an object. This is done with the SetCursor method:

The argument cursor is the type of cursor. It may be:

kBottomLeft, kBottomRight, kTopLeft,

kTopRight, kBottomSide, kLeftSide,

kTopSide, kRightSide, kMove,

kCross, kArrowHor, kArrowVer,

kHand, kRotate, kPointer,

kArrowRight, kCaret, kWatchThey are defined in TVirtualX.h and again we hope the names are self-explanatory. If not, try them by designing a small class. It may derive from something already known like TLine.

Note that the ExecuteEvent() functions may in turn; invoke such functions for other objects, in case an object is drawn using other objects. You can also exploit at best the virtues of inheritance. See for example how the class TArrow (derived from TLine) use or redefine the picking functions in its base class.

The last comment is that mouse position is always given in pixel units in all these standard functions. px=0 and py=0 corresponds to the top-left corner of the canvas. Here, we have followed the standard convention in windowing systems. Note that user coordinates in a canvas (pad) have the origin at the bottom-left corner of the canvas (pad). This is all explained in the paragraph “The Coordinate Systems of a Pad”.

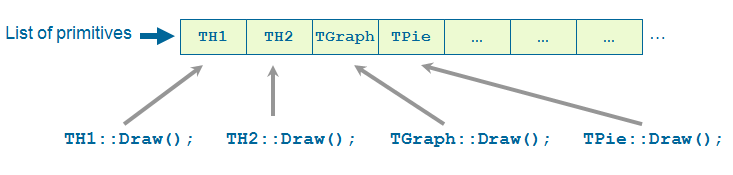

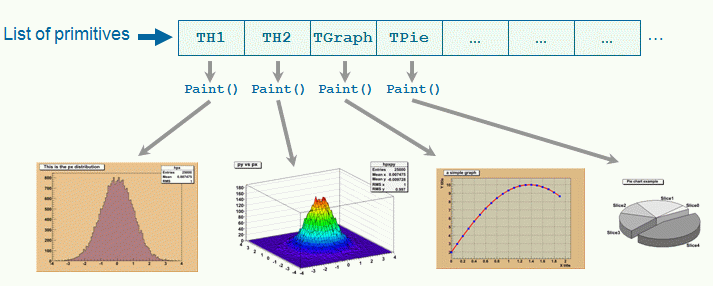

We have talked a lot about canvases, which may be seen as windows. More generally, a graphical entity that contains graphical objects is called a Pad. A Canvas is a special kind of Pad. From now on, when we say something about pads, this also applies to canvases. A pad (class TPad) is a graphical container in the sense it contains other graphical objects like histograms and arrows. It may contain other pads (sub-pads) as well. A Pad is a linked list of primitives of any type (graphs, histograms, shapes, tracks, etc.). It is a kind of display list.

Drawing an object is nothing more than adding its pointer to this list. Look for example at the code of TH1::Draw(). It is merely ten lines of code. The last statement is AppendPad(). This statement calls method of TObject that just adds the pointer of the object, here a histogram, to the list of objects attached to the current pad. Since this is a TObject’s method, every object may be “drawn”, which means attached to a pad.

When is the painting done then ? The answer is: when needed. Every object that derives from TObject has a Paint() method. It may be empty, but for graphical objects, this routine contains all the instructions to paint effectively it in the active pad. Since a Pad has the list of objects it owns, it will call successively the Paint() method of each object, thus re-painting the whole pad on the screen. If the object is a sub-pad, its Paint() method will call the Paint() method of the objects attached, recursively calling Paint() for all the objects.

In some cases a pad need to be painted during a macro execution. To force the pad painting gPad->Update() (see next section) should be performed.

The list of primitives stored in the pad is also used to pick objects and to interact with them.

When an object is drawn, it is always in the so-called active pad. For every day use, it is comfortable to be able to access the active pad, whatever it is. For that purpose, there is a global pointer, called gPad. It is always pointing to the active pad. If you want to change the fill color of the active pad to blue but you do not know its name, do this.

To get the list of colors, go to the paragraph “Color and color palettes” or if you have an opened canvas, click on the View menu, selecting the Colors item.

Now that we have a pointer to the active pad, gPad and that we know this pad contains some objects, it is sometimes interesting to access one of those objects. The method GetPrimitive() of TPad, i.e. TPad::GetPrimitive(const char* name) does exactly this. Since most of the objects that a pad contains derive from TObject, they have a name. The following statement will return a pointer to the object myobjectname and put that pointer into the variable obj. As you can see, the type of returned pointer is TObject*.

Even if your object is something more complicated, like a histogram TH1F, this is normal. A function cannot return more than one type. So the one chosen was the lowest common denominator to all possible classes, the class from which everything derives, TObject. How do we get the right pointer then? Simply do a cast of the function output that will transform the output (pointer) into the right type. For example if the object is a TPaveLabel:

This works for all objects deriving from TObject. However, a question remains. An object has a name if it derives from TNamed, not from TObject. For example, an arrow (TArrow) doesn’t have a name. In that case, the “name” is the name of the class. To know the name of an object, just click with the right button on it. The name appears at the top of the context menu. In case of multiple unnamed objects, a call to GetPrimitive("className") returns the instance of the class that was first created. To retrieve a later instance you can use GetListOfPrimitives(), which returns a list of all the objects on the pad. From the list you can select the object you need.

Hiding an object in a pad can be made by removing it from the list of objects owned by that pad. This list is accessible by the GetListOfPrimitives() method of TPad. This method returns a pointer to a TList. Suppose we get the pointer to the object, we want to hide, call it obj (see paragraph above). We get the pointer to the list:

Then remove the object from this list:

The object will disappear from the pad as soon as the pad is updated (try to resize it for example). If one wants to make the object reappear:

Caution, this will not work with composed objects, for example many histograms drawn on the same plot (with the option “same”). There are other ways! Try to use the method described here for simple objects.

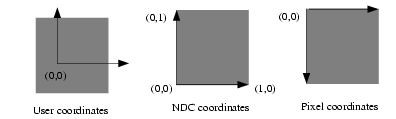

There are coordinate systems in a TPad: user coordinates, normalized coordinates (NDC), and pixel coordinates.

The most common is the user coordinate system. Most methods of TPad use the user coordinates, and all graphic primitives have their parameters defined in terms of user coordinates. By default, when an empty pad is drawn, the user coordinates are set to a range from 0 to 1 starting at the lower left corner. At this point they are equivalent of the NDC coordinates (see below). If you draw a high level graphical object, such as a histogram or a function, the user coordinates are set to the coordinates of the histogram. Therefore, when you set a point it will be in the histogram coordinates.

For a newly created blank pad, one may use TPad::Range to set the user coordinate system. This function is defined as:

The arguments x1, x2 defines the new range in the x direction, and the y1, y2 define the new range in the y-direction.

This will set the active pad to have both coordinates to go from -100 to 100, with the center of the pad at (0,0). You can visually check the coordinates by viewing the status bar in the canvas. To display the status bar select Event Status entry in the View canvas menu.

Normalized coordinates are independent of the window size and of the user system. The coordinates range from 0 to 1 and (0, 0) corresponds to the bottom-left corner of the pad. Several internal ROOT functions use the NDC system (3D primitives, PostScript, log scale mapping to linear scale). You may want to use this system if the user coordinates are not known ahead of time.

The least common is the pixel coordinate system, used by functions such as DistancetoPrimitive() and ExecuteEvent(). Its primary use is for cursor position, which is always given in pixel coordinates. If (px,py) is the cursor position, px=0 and py=0 corresponds to the top-left corner of the pad, which is the standard convention in windowing systems.

Most of the time, you will be using the user coordinate system. But sometimes, you will want to use NDC. For example, if you want to draw text always at the same place over a histogram, no matter what the histogram coordinates are. There are two ways to do this. You can set the NDC for one object or may convert NDC to user coordinates. Most graphical objects offer an option to be drawn in NDC. For instance, a line (TLine) may be drawn in NDC by using DrawLineNDC(). A latex formula or a text may use TText::SetNDC() to be drawn in NDC coordinates.

There are a few utility functions in TPad to convert from one system of coordinates to another. In the following table, a point is defined by (px,py) in pixel coordinates, (ux,uy) in user coordinates, (ndcx,ndcy) in normalized coordinates, (apx, apy) are in absolute pixel coordinates.

| Conversion | TPad’s Methods | Returns |

| NDC to Pixel |

|

Int_t Int_t |

| Pixel to User |

|

Double_t Double_t Double_t ux,uy |

| User to Pixel |

|

Int_t Int_t Int_t px,py |

| User to absolute pixel |

|

Int_t Int_t Int_t apx,apy |

| Absolute pixel to user |

|

Double_t Double_t Double_t ux,uy |

Note: all the pixel conversion functions along the Y axis consider that py=0 is at the top of the pad except PixeltoY() which assume that the position py=0 is at the bottom of the pad. To make PixeltoY() converting the same way as the other conversion functions, it should be used the following way (p is a pointer to a TPad):

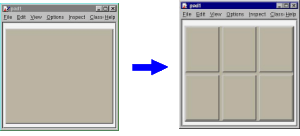

Dividing a pad into sub pads in order for instance to draw a few histograms, may be done in two ways. The first is to build pad objects and to draw them into a parent pad, which may be a canvas. The second is to automatically divide a pad into horizontal and vertical sub pads.

The simplest way to divide a pad is to build sub-pads in it. However, this forces the user to explicitly indicate the size and position of those sub-pads. Suppose we want to build a sub-pad in the active pad (pointed by gPad). First, we build it, using a TPad constructor:

One gives the coordinates of the lower left point (0.1, 0.1) and of the upper right one (0.5, 0.5). These coordinates are in NDC. This means that they are independent of the user coordinates system, in particular if you have already drawn for example a histogram in the mother pad. The only thing left is to draw the pad:

If you want more sub-pads, you have to repeat this procedure as many times as necessary.

The manual way of dividing a pad into sub-pads is sometimes very tedious. There is a way to automatically generate horizontal and vertical sub-pads inside a given pad.

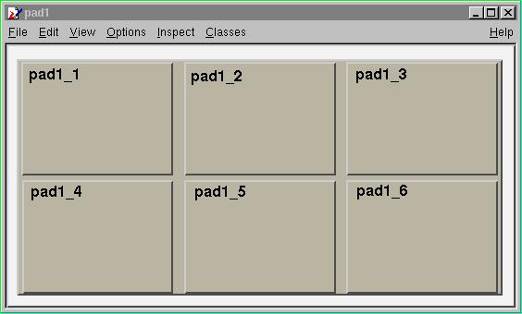

If pad1 is a pad then, it will divide the pad into 3 columns of 2 sub-pads. The generated sub-pads get names pad1_i where the index i=1 to nxm (in our case pad1_1, pad1_2…pad1_6). The names pad1_1etc… correspond to new variables in Cling, so you may use them as soon as the executed method was pad->Divide(). However, in a compiled program, one has to access these objects. Remember that a pad contains other objects and that these objects may themselves be pads. So we can use the GetPrimitive() method:

One question remains. In case one does an automatic divide, how one can set the default margins between pads? This is done by adding two parameters to Divide(), which are the margins in x and y:

The margins are here set to 10% of the parent pad width.

For performance reasons, a pad is not updated with every change. For example, changing the coordinates of the pad does not automatically redraw it. Instead, the pad has a “bit-modified” that triggers a redraw. This bit is automatically set by:

Touching the pad with the mouse - for example resizing it with the mouse.

Finishing the execution of a script.

Adding a new primitive or modifying some primitives for example the name and title of an object.

You can also set the “bit-modified” explicitly with the Modified method:

// the pad has changed

root[] pad1->Modified()

// recursively update all modified pads:

root[] c1->Update()A subsequent call to TCanvas::Update() scans the list of sub-pads and repaints the pads declared modified.

In compiled code or in a long macro, you may want to access an object created during the paint process. To do so, you can force the painting with a TCanvas::Update(). For example, a TGraph creates a histogram (TH1) to paint itself. In this case the internal histogram obtained with TGraph::GetHistogram() is created only after the pad is painted. The pad is painted automatically after the script is finished executing or if you force the painting with TPad::Modified() followed by a TCanvas::Update(). Note that it is not necessary to call TPad::Modified() after a call to Draw(). The “bit-modified” is set automatically by Draw(). A note about the “bit-modified” in sub pads: when you want to update a sub pad in your canvas, you need to call pad->Modified() rather than canvas->Modified(), and follow it with a canvas->Update(). If you use canvas->Modified(), followed by a call to canvas->Update(), the sub pad has not been declared modified and it will not be updated. Also note that a call to pad->Update() where pad is a sub pad of canvas, calls canvas->Update() and recursively updates all the pads on the canvas.

As we will see in the paragraph “Fill Attributes”, a fill style (type of hatching) may be set for a pad.

This is done with the SetFillStyle method where istyle is a style number, defined in “Fill Attributes”. A special set of styles allows handling of various levels of transparency. These are styles number 4000 to 4100, 4000 being fully transparent and 4100 fully opaque. So, suppose you have an existing canvas with several pads. You create a new pad (transparent) covering for example the entire canvas. Then you draw your primitives in this pad. The same can be achieved with the graphics editor. For example:

root[] .x tutorials/hist/h1draw.C

root[] TPad *newpad=new TPad("newpad","Transparent pad",0,0,1,1);

root[] newpad->SetFillStyle(4000);

root[] newpad->Draw();

root[] newpad->cd();

root[] // create some primitives, etcSetting the scale to logarithmic or linear is an attribute of the pad, not the axis or the histogram. The scale is an attribute of the pad because you may want to draw the same histogram in linear scale in one pad and in log scale in another pad. Frequently, we see several histograms on top of each other in the same pad. It would be very inconvenient to set the scale attribute for each histogram in a pad.

Furthermore, if the logic was set in the histogram class (or each object) the scale setting in each Paint method of all objects should be tested.

If you have a pad with a histogram, a right-click on the pad, outside of the histograms frame will convince you. The SetLogx(), SetLogy() and SetLogz() methods are there. As you see, TPad defines log scale for the two directions x and y plus z if you want to draw a 3D representation of some function or histogram.

The way to set log scale in the x direction for the active pad is:

To reset log in the z direction:

If you have a divided pad, you need to set the scale on each of the sub-pads. Setting it on the containing pad does not automatically propagate to the sub-pads. Here is an example of how to set the log scale for the x-axis on a canvas with four sub-pads:

root[] TCanvas MyCanvas("MyCanvas","My Canvas")

root[] MyCanvas->Divide(2,2)

root[] MyCanvas->cd(1)

root[] gPad->SetLogx()

root[] MyCanvas->cd(2)

root[] gPad->SetLogx()

root[] MyCanvas->cd(3)

root[] gPad->SetLogx()When the TPad::WaitPrimitive() method is called with no arguments, it will wait until a double click or any key pressed is executed in the canvas. A call to gSystem->Sleep(10) has been added in the loop to avoid consuming at all the CPU. This new option is convenient when executing a macro. By adding statements like:

You can monitor the progress of a running macro, stop it at convenient places with the possibility to interact with the canvas and resume the execution with a double click or a key press.

You can make the TPad non-editable. Then no new objects can be added, and the existing objects and the pad can not be changed with the mouse or programmatically. By default the TPad is editable.

In this paragraph, we describe the various simple 2D graphical objects defined in ROOT. Usually, one defines these objects with their constructor and draws them with their Draw() method. Therefore, the examples will be very brief. Most graphical objects have line and fill attributes (color, width) that will be described in “Graphical objects attributes”. If the user wants more information, the class names are given and they may refer to the online developer documentation. This is especially true for functions and methods that set and get internal values of the objects described here. By default 2D graphical objects are created in User Coordinates with (0, 0) in the lower left corner.

The simplest graphical object is a line. It is implemented in the TLine class. The line constructor is:

The arguments x1, y1, x2, y2 are the coordinates of the first and second point. It can be used:

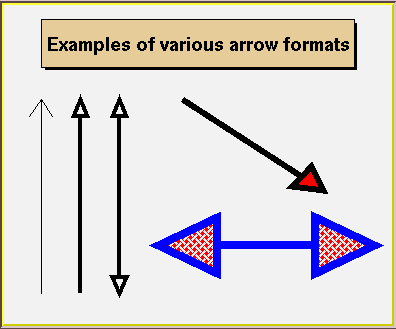

The arrow constructor is:

It defines an arrow between points x1,y1 and x2,y2. The arrow size is in percentage of the pad height. The option parameter has the following meanings:

“>”

“>”

“<|”

“<|”

“<”

“<”

“|>”

“|>”

“<>”

“<>”

“<|>”

“<|>”

Once an arrow is drawn on the screen, one can:

click on one of the edges and move this edge.

click on any other arrow part to move the entire arrow.

If FillColor is 0, an open triangle is drawn; else a full triangle is filled with the set fill color. If ar is an arrow object, fill color is set with:

Where icolor is the color defined in “Color and Color Palettes”.

The default-opening angle between the two sides of the arrow is 60 degrees. It can be changed with the method ar->SetAngle(angle), where angle is expressed in degrees.

A poly-line is a set of joint segments. It is defined by a set of N points in a 2D space. Its constructor is:

Where n is the number of points, and x and y are arrays of n elements with the coordinates of the points. TPolyLine can be used by it self, but is also a base class for other objects, such as curly arcs.

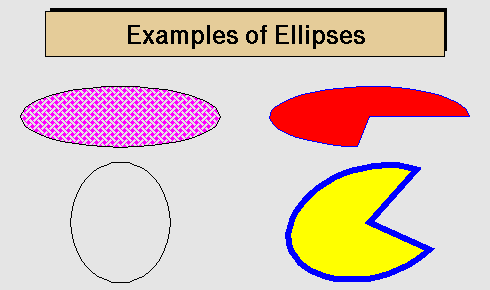

An ellipse can be truncated and rotated. It is defined by its center (x1,y1) and two radii r1 and r2. A minimum and maximum angle may be specified (phimin,phimax). The ellipse may be rotated with an angle theta. All these angles are in degrees. The attributes of the outline line are set via TAttLine, of the fill area - via TAttFill class. They are described in “Graphical Objects Attributes”.

When an ellipse sector is drawn only, the lines between the center and the end points of the sector are drawn by default. By specifying the drawn option “only”, these lines can be avoided. Alternatively, the method SetNoEdges() can be called. To remove completely the ellipse outline, specify zero (0) as a line style.

The TEllipse constructor is:

TEllipse(Double_t x1, Double_t y1, Double_t r1, Double_t r2,

Double_t phimin, Double_t phimax, Double_t theta)An ellipse may be created with:

The class TBox defines a rectangle. It is a base class for many different higher-level graphical primitives. Its bottom left coordinates x1, y1 and its top right coordinates x2, y2, defines a box. The constructor is:

It may be used as in:

A TWbox is a rectangle (TBox) with a border size and a border mode. The attributes of the outline line and of the fill area are described in “Graphical Objects Attributes”

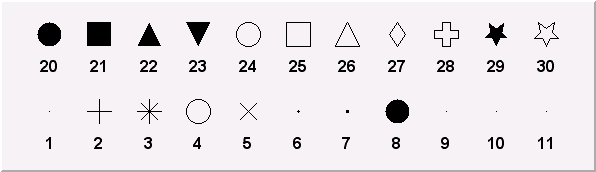

A marker is a point with a fancy shape! The possible markers are shown in the next figure.

The marker constructor is:

The parameters x and y are the marker coordinates and marker is the marker type, shown in the previous figure. Suppose the pointer ma is a valid marker. The marker size is set via ma->SetMarkerSize(size), where size is the desired size. Note, that the marker types 1, 6 and 7 (the dots) cannot be scaled. They are always drawn with the same number of pixels. SetMarkerSize does not apply on them. To have a “scalable dot” a circle shape should be used instead, for example, the marker type 20. The default marker type is 1, if SetMarkerStyle is not specified. It is the most common one to draw scatter plots.

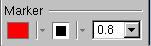

The user interface for changing the marker color, style and size looks like shown in this picture. It takes place in the editor frame anytime the selected object inherits the class TAttMarker.

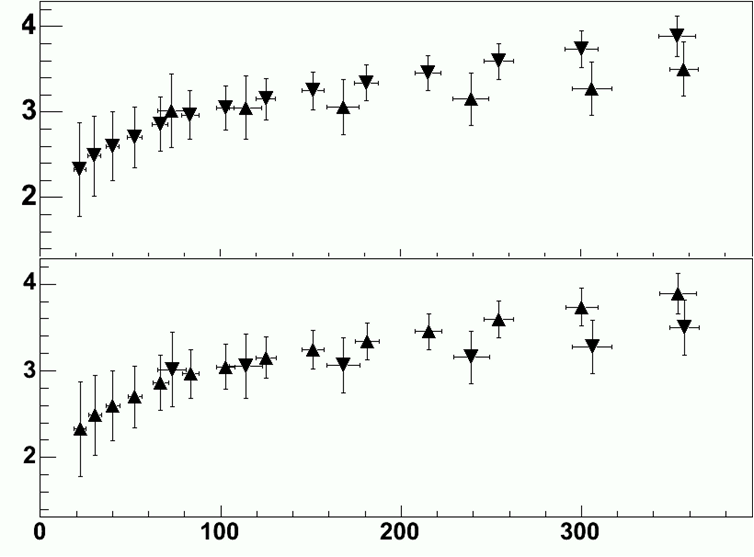

Non-symmetric symbols should be used carefully in plotting. The next two graphs show how the misleading a careless use of symbols can be. The two plots represent the same data sets but because of a bad symbol choice, the two on the top appear further apart from the next example.

A TPolyMaker is defined by an array on N points in a 2D space. At each point x[i], y[i] a marker is drawn. The list of marker types is shown in the previous paragraph. The marker attributes are managed by the class TAttMarker and are described in “Graphical Objects Attributes”. The TPolyMarker constructor is:

Where x and y are arrays of coordinates for the n points that form the poly-marker.

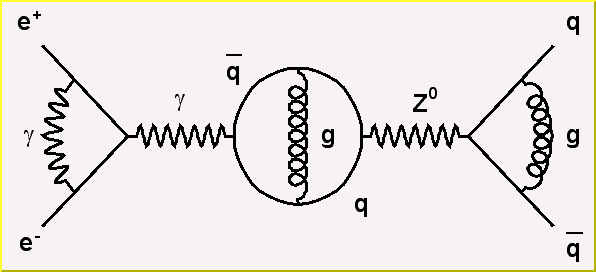

This is a peculiarity of particle physics, but we do need sometimes to draw Feynman diagrams. Our friends working in banking can skip this part. A set of classes implements curly or wavy poly-lines typically used to draw Feynman diagrams. Amplitudes and wavelengths may be specified in the constructors, via commands or interactively from context menus. These classes are TCurlyLine and TCurlyArc. These classes make use of TPolyLine by inheritance; ExecuteEvent methods are highly inspired from the methods used in TPolyLine and TArc.

The TCurlyLine constructor is:

TCurlyLine(Double_t x1, Double_t y1, Double_t x2, Double_t y2,

Double_t wavelength, Double_t amplitude)The coordinates (x1, y1) define the starting point, (x2, y2) - the end-point. The wavelength and the amplitude are given in percent of the pad height.

The TCurlyArc constructor is:

TCurlyArc(Double_t x1, Double_t y1, Double_t rad,

Double_t phimin, Double_t phimax,

Double_t wavelength, Double_t amplitude)The curly arc center is (x1, y1) and the radius is rad. The wavelength and the amplitude are given in percent of the line length. The parameters phimin and phimax are the starting and ending angle of the arc (given in degrees). Refer to $ROOTSYS/tutorials/visualisation/graphics/feynman.C for the script that built the figure above.

Text displayed in a pad may be embedded into boxes, called paves (TPaveLabel), or titles of graphs or many other objects but it can live a life of its own. All text displayed in ROOT graphics is an object of class TText. For a physicist, it will be most of the time a TLatex expression (which derives from TText). TLatex has been conceived to draw mathematical formulas or equations. Its syntax is very similar to the Latex in mathematical mode.

Subscripts and superscripts are made with the _ and ^ commands. These commands can be combined to make complex subscript and superscript expressions. You may choose how to display subscripts and superscripts using the 2 functions SetIndiceSize(Double_t) and SetLimitIndiceSize(Int_t). Examples of what can be obtained using subscripts and superscripts:

| The expression | Gives | The expression | Gives | The expression | Gives |

x^{2y} |

\(x^{2y}\) | x^{y^{2}} |

\(x^{y^{2}}\) | x_{1}^{y_{1}} |

\(x_{1}^{y_{1}}\) |

x_{2y} |

\(x_{2y}\) | x^{y_{1}} |

\(x^{y_{1}}\) | x_{1}^{y} |

\(x_{1}^{y}\) |

Fractions denoted by the / symbol are made in the obvious way. The #frac command is used for large fractions in displayed formula; it has two arguments: the numerator and the denominator. For example, the equation x = y + z 2 y 2 + 1 is obtained by following expression x=#frac{y+z/2}{y^{2}+1}.

The #sqrt command produces the square ROOT of its argument; it has an optional first argument for other roots.

Example: #sqrt{10} #sqrt[3]{10}

You can produce three kinds of proportional delimiters.

#[]{....} or “à la” Latex

#left[.....#right]big square brackets

#{}{....} or #left{.....#right}big curly brackets

#||{....} or #left|.....#right|big absolute value symbol

#(){....} or #left(.....#right)big parenthesis

You can change the font and the text color at any moment using:

#font[font-number]{...} and #color[color-number]{...}

A TLatex string may be split in two with the following command: #splitline{top}{bottom}. TAxis and TGaxis objects can take advantage of this feature. For example, the date and time could be shown in the time axis over two lines with: #splitline{21 April 2003}{14:23:56}

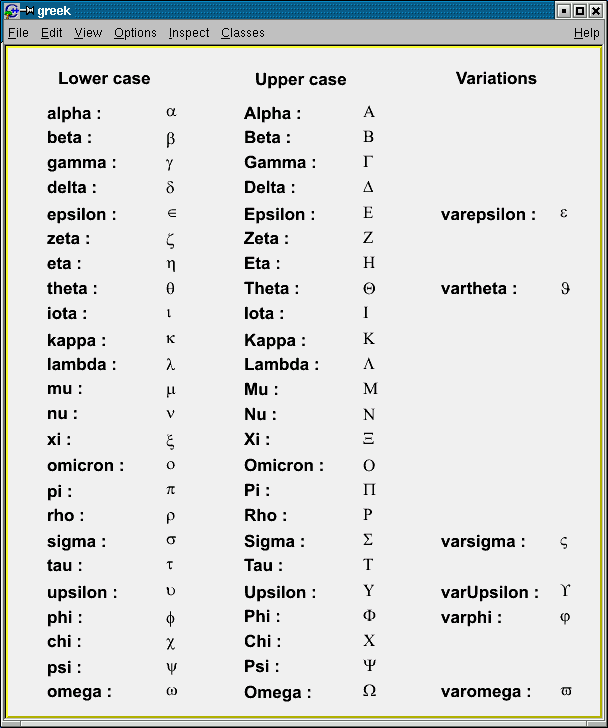

The command to produce a lowercase Greek letter is obtained by adding # to the name of the letter. For an uppercase Greek letter, just capitalize the first letter of the command name.

#alpha #beta #chi #delta #varepsilon #phi

#gamma #eta #iota #varphi #kappa #lambda

#mu #nu #omicron #pi #theta #rho

#sigma #tau #upsilon #varomega #omega #xi

#psi #zeta #Alpha #Beta #Chi #Delta

#Epsilon #Phi #Gamma #Eta #Iota #Kappa

#vartheta #Lambda #Mu #Nu #Omicron #Pi

#Theta #Rho #Sigma #Tau #Upsilon #Omega

#varsigma #Xi #Psi #epsilon #varUpsilon #Zeta

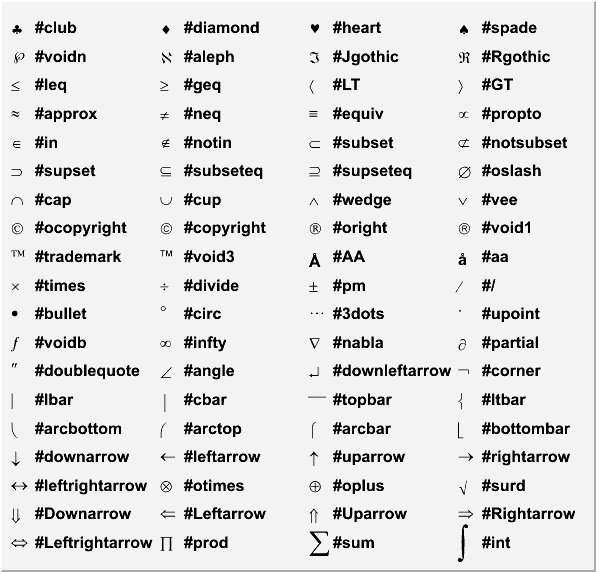

TLatex can make mathematical and other symbols. A few of them, such as + and >, are produced by typing the corresponding keyboard character. Others are obtained with the commands as shown in the table above.

Symbols in a formula are sometimes placed one above another. TLatex provides special commands for that.

#hat{a} =hat

#check =inverted hat

#acute =acute

#grave =accent grave

#dot =derivative

#ddot =double derivative

#tilde =tilde

#slash =special sign. Draw a slash on top of the text between brackets for example

#slash{E}_{T}generates “Missing ET”

a _ is obtained with #bar{a}

a -> is obtained with #vec{a}

The script $ROOTSYS/tutorials/visualisation/graphics/latex.C:

{

TCanvas c1("c1","Latex",600,700);

TLatex l;

l.SetTextAlign(12);

l.SetTextSize(0.04);

l.DrawLatex(0.1,0.8,"1) C(x) = d #sqrt{#frac{2}{#lambdaD}}

#int^{x}_{0}cos(#frac{#pi}{2}t^{2})dt");

l.DrawLatex(0.1,0.6,"2) C(x) = d #sqrt{#frac{2}{#lambdaD}}

#int^{x}cos(#frac{#pi}{2}t^{2})dt");

l.DrawLatex(0.1,0.4,"3) R = |A|^{2} =

#frac{1}{2}(#[]{#frac{1}{2}+C(V)}^{2}+

#[]{#frac{1}{2}+S(V)}^{2})");

l.DrawLatex(0.1,0.2,"4) F(t) = #sum_{i=

-#infty}^{#infty}A(i)cos#[]{#frac{i}{t+i}}");

}

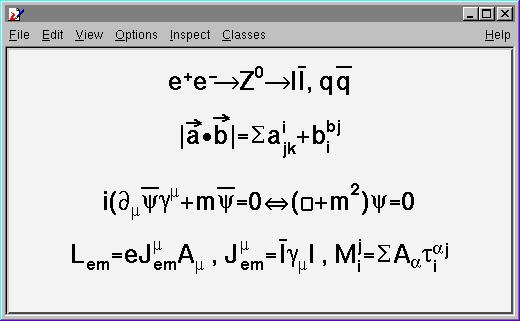

The script $ROOTSYS/tutorials/visualisation/graphics/latex2.C:

{

TCanvas c1("c1","Latex",600,700);

TLatex l;

l.SetTextAlign(23);

l.SetTextSize(0.1);

l.DrawLatex(0.5,0.95,"e^{+}e^{-}#rightarrowZ^{0}

#rightarrowI#bar{I}, q#bar{q}");

l.DrawLatex(0.5,0.75,"|#vec{a}#bullet#vec{b}|=

#Sigmaa^{i}_{jk}+b^{bj}_{i}");

l.DrawLatex(0.5,0.5,"i(#partial_{#mu}#bar{#psi}#gamma^{#mu}

+m#bar{#psi}=0

#Leftrightarrow(#Box+m^{2})#psi=0");

l.DrawLatex(0.5,0.3,"L_{em}=eJ^{#mu}_{em}A_{#mu} ,

J^{#mu}_{em}=#bar{I}#gamma_{#mu}I

M^{j}_{i}=#SigmaA_{#alpha}#tau^{#alphaj}_{i}");

}

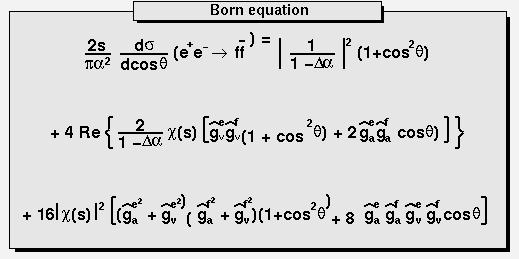

The script $ROOTSYS/tutorials/visualisation/graphics/latex3.C:

{

TCanvas c1("c1");

TPaveText pt(.1,.5,.9,.9);

pt.AddText("#frac{2s}{#pi#alpha^{2}}

#frac{d#sigma}{dcos#theta} (e^{+}e^{-}

#rightarrow f#bar{f} ) = ");

pt.AddText("#left| #frac{1}{1 - #Delta#alpha} #right|^{2}

(1+cos^{2}#theta");

pt.AddText("+ 4 Re #left{ #frac{2}{1 - #Delta#alpha} #chi(s)

#[]{#hat{g}_{#nu}^{e}#hat{g}_{#nu}^{f}

(1 + cos^{2}#theta) + 2 #hat{g}_{a}^{e}

#hat{g}_{a}^{f} cos#theta) } #right}");

pt.SetLabel("Born equation");

pt.Draw();

}

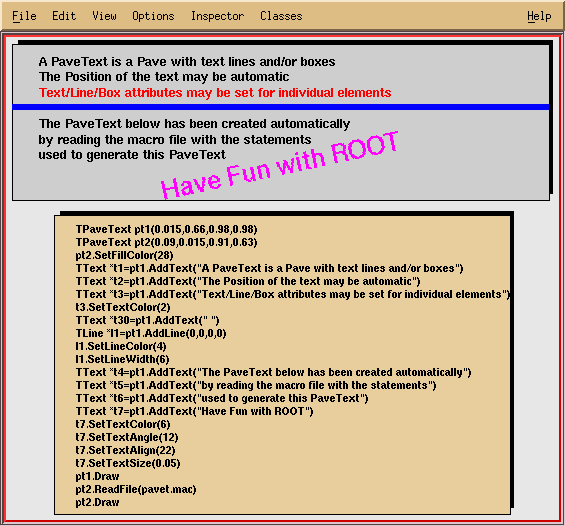

Text displayed in a pad may be embedded into boxes, called paves, or may be drawn alone. In any case, it is recommended to use a Latex expression, which is covered in the previous paragraph. Using TLatex is valid whether the text is embedded or not. In fact, you will use Latex expressions without knowing it since it is the standard for all the embedded text. A pave is just a box with a border size and a shadow option. The options common to all types of paves and used when building those objects are the following:

option = "T" top frame

option = "B" bottom frame

option = "R" right frame

option = "L" left frame

option = "NDC" x1,y1,x2,y2 are given in NDC

option = "ARC" corners are rounded

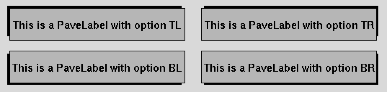

We will see the practical use of these options in the description of the more functional objects like TPaveLabels. There are several categories of paves containing text: TPaveLabel, TPaveText and TPavesText. TPaveLabels are panels containing one line of text. They are used for labeling.

Where (x1, y1) are the coordinates of the bottom left corner, (x2,y2) - coordinates of the upper right corner. “label” is the text to be displayed and “option” is the drawing option, described above. By default, the border size is 5 and the option is “br”. If one wants to set the border size to some other value, one may use the method SetBorderSize(). For example, suppose we have a histogram, which limits are (-100,100) in the x direction and (0, 1000) in the y direction. The following lines will draw a label in the center of the histogram, with no border. If one wants the label position to be independent of the histogram coordinates, or user coordinates, one can use the option “NDC”. See “The Coordinate Systems of a Pad”.

PaveLabels drawn with different optionsA TPaveLabel can contain only one line of text. A TPaveText may contain several lines. This is the only difference. This picture illustrates and explains some of the points of TPaveText. Once a TPaveText is drawn, a line can be added or removed by brining up the context menu with the mouse.

A TPavesText is a stack of text panels (see TPaveText). One can set the number of stacked panels at building time. It has the following constructor: By default, the number of stacked panels is 5, option=“br”.

TMathText’s purpose is to write mathematical equations, exactly as TeX would do it. The syntax is the same as the TeX’s one.

The script $ROOTSYS/tutorials/visualisation/graphics/tmathtex.C:

gives the following output:

TMathText uses plain TeX syntax and uses “\” as control instead of “#”. If a piece of text containing “\” is given to TLatex then TMathText is automatically invoked. Therefore, as histograms’ titles, axis titles, labels etc … are drawn using TLatex, the TMathText syntax can be used for them also.

The axis objects are automatically built by various high level objects such as histograms or graphs. Once build, one may access them and change their characteristics. It is also possible, for some particular purposes to build axis on their own. This may be useful for example in the case one wants to draw two axis for the same plot, one on the left and one on the right.

For historical reasons, there are two classes representing axis. TAxis * axis is the axis object, which will be returned when calling the TH1::GetAxis() method.

Of course, you may do the same for Y and Z-axis. The graphical representation of an axis is done with the TGaxis class. The histogram classes and TGraph generate instances of this class. This is internal and the user should not have to see it.

The axis title is set, as with all named objects, by

When the axis is embedded into a histogram or a graph, one has to first extract the axis object:

The axis options are most simply set with the styles. The available style options controlling specific axis options are the following:

TAxis *axis = histo->GetXaxis();

axis->SetAxisColor(Color_t color = 1);

axis->SetLabelColor(Color_t color = 1);

axis->SetLabelFont(Style_t font = 62);

axis->SetLabelOffset(Float_t offset = 0.005);

axis->SetLabelSize(Float_t size = 0.04);

axis->SetNdivisions(Int_t n = 510, Bool_t optim = kTRUE);

axis->SetNoExponent(Bool_t noExponent = kTRUE);

axis->SetTickLength(Float_t length = 0.03);

axis->SetTitleOffset(Float_t offset = 1);

axis->SetTitleSize(Float_t size = 0.02);The getters corresponding to the described setters are also available. The general options, not specific to axis, as for instance SetTitleTextColor() are valid and do have an effect on axis characteristics.

Use TAxis::SetNdivisions(ndiv,optim) to set the number of divisions for an axis. The ndiv and optim are as follows:

ndiv = N1 + 100*N2 + 10000*N3

N1 = number of first divisions.

N2 = number of secondary divisions.

N3 = number of tertiary divisions.

optim = kTRUE (default), the divisions’ number will be optimized around the specified value.

optim = kFALSE, or n < 0, the axis will be forced to use exactly n divisions.

For example:

ndiv = 0: no tick marks.

ndiv = 2: 2 divisions, one tick mark in the middle of the axis.

ndiv = 510: 10 primary divisions, 5 secondary divisions

ndiv = -10: exactly 10 primary divisions

You can use TAxis::SetRange or TAxis::SetRangeUser to zoom the axis.

The SetRange method parameters are bin numbers. They are not axis. For example if a histogram plots the values from 0 to 500 and has 100 bins, SetRange(0,10) will cover the values 0 to 50. The parameters for SetRangeUser are user coordinates. If the start or end is in the middle of a bin the resulting range is approximation. It finds the low edge bin for the start and the high edge bin for the high.

Both methods, SetRange and SetRangeUser, are in the context menu of any axis and can be used interactively. In addition, you can zoom an axis interactively: click on the axis on the start, drag the cursor to the end, and release the mouse button.

An axis may be drawn independently of a histogram or a graph. This may be useful to draw for example a supplementary axis for a graph. In this case, one has to use the TGaxis class, the graphical representation of an axis. One may use the standard constructor for this kind of objects:

TGaxis(Double_t xmin, Double_t ymin, Double_t xmax, Double_t ymax,

Double_t wmin, Double_t wmax, Int_t ndiv = 510,

Option_t* chopt,Double_t gridlength = 0)The arguments xmin, ymin are the coordinates of the axis’ start in the user coordinates system, and xmax, ymax are the end coordinates. The arguments wmin and wmax are the minimum (at the start) and maximum (at the end) values to be represented on the axis; ndiv is the number of divisions. The options, given by the “chopt” string are the following:

chopt = 'G': logarithmic scale, default is linear.

chopt = 'B': Blank axis (it is useful to superpose the axis).

Instead of the wmin,wmax arguments of the normal constructor, i.e. the limits of the axis, the name of a TF1 function can be specified. This function will be used to map the user coordinates to the axis values and ticks.

The constructor is the following:

TGaxis(Double_t xmin, Double_t ymin, Double_t xmax, Double_t ymax,

const char* funcname, Int_t ndiv=510,

Option_t* chopt, Double_t gridlength=0)In such a way, it is possible to obtain exponential evolution of the tick marks position, or even decreasing. In fact, anything you like.

Tick marks are normally drawn on the positive side of the axis, however, if xmin = xmax, then negative.

chopt = '+': tick marks are drawn on Positive side. (Default)

chopt = '-': tick marks are drawn on the negative side.

chopt = '+-': tick marks are drawn on both sides of the axis.

chopt = ‘U': unlabeled axis, default is labeled.

Labels are normally drawn on side opposite to tick marks. However, chopt = '=': on Equal side. The function TAxis::CenterLabels() sets the bit kCenterLabels and it is visible from TAxis context menu. It centers the bin labels and it makes sense only when the number of bins is equal to the number of tick marks. The class responsible for drawing the axis TGaxis inherits this property.

Labels are normally drawn parallel to the axis. However, if xmin = xmax, then they are drawn orthogonal, and if ymin=ymax they are drawn parallel.

By default, an exponent of the form 10^N is used when the label values are either all very small or very large. One can disable the exponent by calling:

Note that this option is implicitly selected if the number of digits to draw a label is less than the fgMaxDigits global member. If the property SetNoExponent was set in TAxis (via TAxis::SetNoExponent), the TGaxis will inherit this property. TGaxis is the class responsible for drawing the axis. The method SetNoExponent is also available from the axis context menu.

TGaxis::fgMaxDigits is the maximum number of digits permitted for the axis labels above which the notation with 10^N is used. It must be greater than 0. By default fgMaxDigits is 5 and to change it use the TGaxis::SetMaxDigits method. For example to set fgMaxDigits to accept 6 digits and accept numbers like 900000 on an axis call:

Labels are centered on tick marks. However, if xmin = xmax, then they are right adjusted.

chopt = 'R': labels are right adjusted on tick mark (default is centered)

chopt = 'L': labels are left adjusted on tick mark.

chopt = 'C': labels are centered on tick mark.

chopt = 'M': In the Middle of the divisions.

Blank characters are stripped, and then the label is correctly aligned. The dot, if last character of the string, is also stripped. In the following, we have some parameters, like tick marks length and characters height (in percentage of the length of the axis, in user coordinates). The default values are as follows:

Primary tick marks: 3.0 %

Secondary tick marks: 1.5 %

Third order tick marks: .75 %

Characters height for labels: 4%

Labels offset: 1.0 %

Use the TStyle::SetStripDecimals to strip decimals when drawing axis labels. By default, the option is set to true, and TGaxis::PaintAxis removes trailing zeros after the dot in the axis labels, e.g. {0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, etc.}

If this function is called with strip=kFALSE, TGaxis::PaintAxis() will draw labels with the same number of digits after the dot, e.g. {0.0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, etc.}

chopt = 'W': cross-Wire

By default, the axis binning is optimized.

chopt = 'N': No binning optimization

chopt = 'I': Integer labeling

Histograms’ axis can be defined as “time axis”. To do that it is enough to activate the SetTimeDisplay attribute on a given axis. If h is a histogram, it is done the following way:

Two parameters can be adjusted in order to define time axis: the time format and the time offset.

It defines the format of the labels along the time axis. It can be changed using the TAxis method SetTimeFormat. The time format is the one used by the C function strftime(). It is a string containing the following formatting characters:

| For the date: | %a abbreviated weekday name %b abbreviated month name %d day of the month (01-31) %m month (01-12) %y year without century %Y year with century |

| For the time: | %H hour (24-hour clock) %I hour (12-hour clock) %p local equivalent of AM or PM %M minute (00-59) %S seconds (00-61) %% % |

The other characters are output as is. For example to have a format like dd/mm/yyyy one should do:

If the time format is not defined, a default one will be computed automatically.

This is a time in seconds in the UNIX standard UTC format (the universal time, not the local one), defining the starting date of a histogram axis. This date should be greater than 01/01/95 and is given in seconds. There are three ways to define the time offset:

1- By setting the global default time offset:

If no time offset is defined for a particular axis, the default time offset will be used. In the example above, notice the usage of TDatime to translate an explicit date into the time in seconds required by SetTimeFormat.

2- By setting a time offset to a particular axis:

3- Together with the time format using SetTimeFormat. The time offset can be specified using the control character %F after the normal time format. %F is followed by the date in the format: yyyy-mm-dd hh:mm:ss.

Notice that this date format is the same used by the TDatime function AsSQLString. If needed, this function can be used to translate a time in seconds into a character string which can be appended after %F. If the time format is not specified (before %F) the automatic one will be used. The following example illustrates the various possibilities.

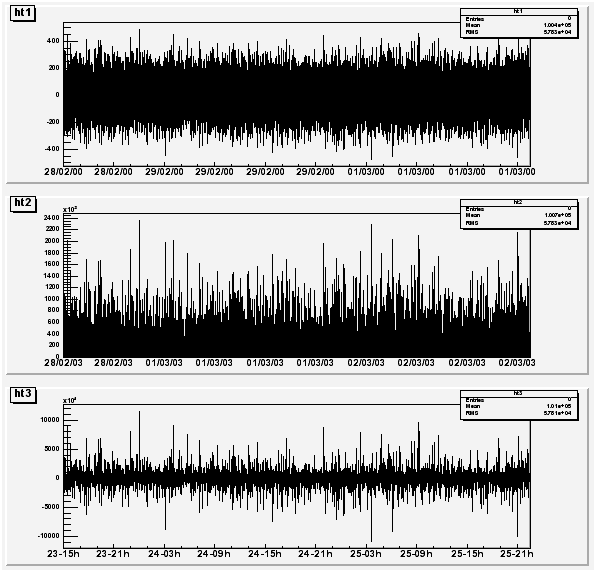

{

gStyle->SetTitleH(0.08);

TDatime da(2003,02,28,12,00,00);

gStyle->SetTimeOffset(da.Convert());

ct = new TCanvas("ct","Time on axis",0,0,600,600);

ct->Divide(1,3);

ht1 = new TH1F("ht1","ht1",30000,0.,200000.);

ht2 = new TH1F("ht2","ht2",30000,0.,200000.);

ht3 = new TH1F("ht3","ht3",30000,0.,200000.);

for (Int_t i=1;i<30000;i++) {

Float_t noise = gRandom->Gaus(0,120);

ht1->SetBinContent(i,noise);

ht2->SetBinContent(i,noise*noise);

ht3->SetBinContent(i,noise*noise*noise);

}

ct->cd(1);

ht1->GetXaxis()->SetLabelSize(0.06);

ht1->GetXaxis()->SetTimeDisplay(1);

ht1->GetXaxis()->SetTimeFormat("%d/%m/%y%F2000-02-2813:00:01");

ht1->Draw();

ct->cd(2);

ht2->GetXaxis()->SetLabelSize(0.06);

ht2->GetXaxis()->SetTimeDisplay(1);

ht2->GetXaxis()->SetTimeFormat("%d/%m/%y");

ht2->Draw();

ct->cd(3);

ht3->GetXaxis()->SetLabelSize(0.06);

TDatime dh(2001,09,23,15,00,00);

ht3->GetXaxis()->SetTimeDisplay(1);

ht3->GetXaxis()->SetTimeOffset(dh.Convert());

ht3->Draw();

}The output is shown in the figure below. If a time axis has no specified time offset, the global time offset will be stored in the axis data structure. The histogram limits are in seconds. If wmin and wmax are the histogram limits, the time axis will spread around the time offset value from TimeOffset+wmin to TimeOffset+wmax. Until now all examples had a lowest value equal to 0. The following example demonstrates how to define the histogram limits relatively to the time offset value.

{

// Define the time offset as 2003, January 1st

TDatime T0(2003,01,01,00,00,00);

int X0 = T0.Convert();

gStyle->SetTimeOffset(X0);

// Define the lowest histogram limit as 2002,September 23rd

TDatime T1(2002,09,23,00,00,00);

int X1 = T1.Convert()-X0;

// Define the highest histogram limit as 2003, March 7th

TDatime T2(2003,03,07,00,00,00);

int X2 = T2.Convert(1)-X0;

TH1F * h1 = new TH1F("h1","test",100,X1,X2);

TRandom r;

for (Int_t i=0;i<30000;i++) {

Double_t noise = r.Gaus(0.5*(X1+X2),0.1*(X2-X1));

h1->Fill(noise);

}

h1->GetXaxis()->SetTimeDisplay(1);

h1->GetXaxis()->SetLabelSize(0.03);

h1->GetXaxis()->SetTimeFormat("%Y/%m/%d");

h1->Draw();

}The output is shown in the next figure. Usually time axes are created automatically via histograms, but one may also want to draw a time axis outside a “histogram context”. Therefore, it is useful to understand how TGaxis works for such axis. The time offset can be defined using one of the three methods described before. The time axis will spread around the time offset value. Actually, it will go from TimeOffset+wmin to TimeOffset+wmax where wmin and wmax are the minimum and maximum values (in seconds) of the axis. Let us take again an example. Having defined “2003, February 28 at 12h”, we would like to see the axis a day before and a day after.

A TGaxis can be created the following way (a day has 86400 seconds):

the “t” option (in lower case) means it is a “time axis”. The axis goes form 100000 seconds before TimeOffset and 150000 seconds after. So the complete macro is:

{

c1 = new TCanvas("c1","Examples of TGaxis",10,10,700,500);

c1->Range(-10,-1,10,1);

TGaxis *axis = new TGaxis(-8,-0.6,8,-0.6,-100000,150000,2405,"t");

axis->SetLabelSize(0.03);

TDatime da(2003,02,28,12,00,00);

axis->SetTimeOffset(da.Convert());

axis->SetTimeFormat("%d/%m/%Y");

axis->Draw();

}The time format is specified with:

The macro gives the following output:

Thanks to the TLatex directive #splitline it is possible to write the time labels on two lines. In the previous example changing the SetTimeFormat line by:

will produce the following axis:

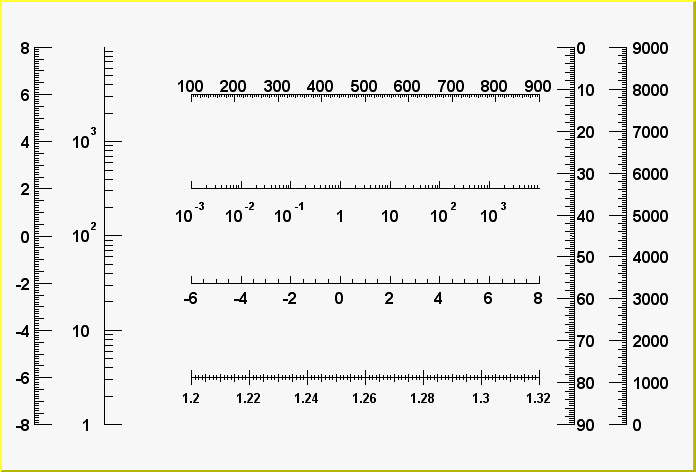

To illustrate what was said, we provide two scripts. The first one creates the picture shown in the next figure.

The first script is:

{

c1 = new TCanvas("c1","Examples of Gaxis",10,10,700,500);

c1->Range(-10,-1,10,1);

TGaxis *axis1 = new TGaxis(-4.5,-0.2,5.5,-0.2,-6,8,510,"");

axis1->SetName("axis1");

axis1->Draw();

TGaxis *axis2 = new TGaxis(4.5,0.2,5.5,0.2,0.001,10000,510,"G");

axis2->SetName("axis2");

axis2->Draw();

TGaxis *axis3 = new TGaxis(-9,-0.8,-9,0.8,-8,8,50510,"");

axis3->SetName("axis3");

axis3->Draw();

TGaxis *axis4 = new TGaxis(-7,-0.8,7,0.8,1,10000,50510,"G");

axis4->SetName("axis4");

axis4->Draw();

TGaxis *axis5 = new TGaxis(-4.5,-6,5.5,-6,1.2,1.32,80506,"-+");

axis5->SetName("axis5");

axis5->SetLabelSize(0.03);

axis5->SetTextFont(72);

axis5->SetLabelOffset(0.025);

axis5->Draw();

TGaxis *axis6 = new TGaxis(-4.5,0.6,5.5,0.6,100,900,50510,"-");

axis6->SetName("axis6");

axis6->Draw();

TGaxis *axis7 = new TGaxis(8,-0.8,8,0.8,0,9000,50510,"+L");

axis7->SetName("axis7");

axis7->SetLabelOffset(0.01);

axis7->Draw();

// One can make a vertical axis going top->bottom.

// However one need to adjust labels align to avoid overlapping.

TGaxis *axis8 = new TGaxis(6.5,0.8,6.5,-0.8,0,90,50510,"-L");

axis8->SetName("axis8");

axis8->Draw();

}

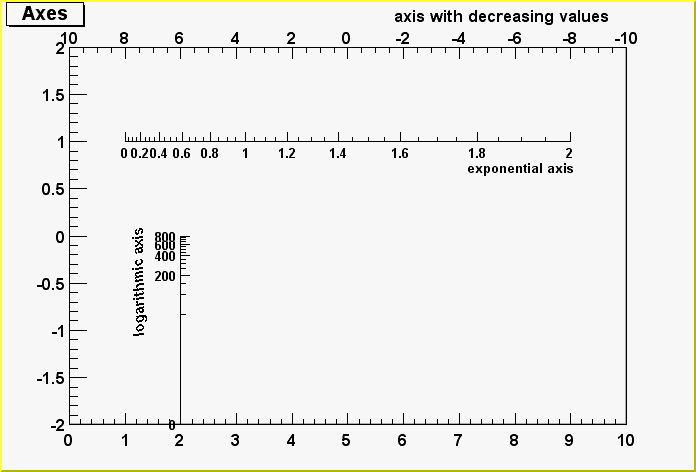

The second example shows the use of the second form of the constructor, with axis ticks position determined by a function TF1:

void gaxis3a()

{

gStyle->SetOptStat(0);

TH2F *h2 = new TH2F("h","Axes",2,0,10,2,-2,2);

h2->Draw();

TF1 *f1=new TF1("f1","-x",-10,10);

TGaxis *A1 = new TGaxis(0,2,10,2,"f1",510,"-");

A1->SetTitle("axis with decreasing values");

A1->Draw();

TF1 *f2=new TF1("f2","exp(x)",0,2);

TGaxis *A2 = new TGaxis(1,1,9,1,"f2");

A2->SetTitle("exponential axis");

A2->SetLabelSize(0.03);

A2->SetTitleSize(0.03);

A2->SetTitleOffset(1.2);

A2->Draw();

TF1 *f3=new TF1("f3","log10(x)",0,800);

TGaxis *A3 = new TGaxis(2,-2,2,0,"f3",505);

A3->SetTitle("logarithmic axis");

A3->SetLabelSize(0.03);

A3->SetTitleSize(0.03);

A3->SetTitleOffset(1.2);

A3->Draw();

}

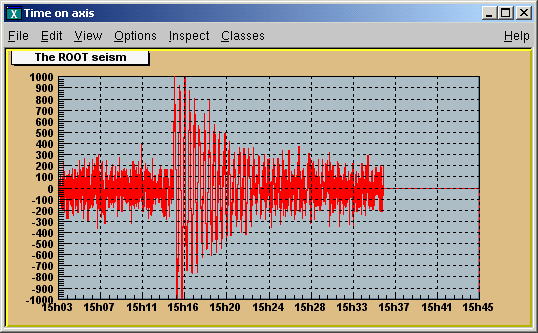

// strip chart example

void seism() {

TStopwatch sw; sw.Start();

//set time offset

TDatime dtime;

gStyle->SetTimeOffset(dtime.Convert());

TCanvas *c1 = new TCanvas("c1","Time on axis",10,10,1000,500);

c1->SetFillColor(42);

c1->SetFrameFillColor(33);

c1->SetGrid();

Float_t bintime = 1;

// one bin = 1 second. change it to set the time scale

TH1F *ht = new TH1F("ht","The ROOT seism",10,0,10*bintime);

Float_t signal = 1000;

ht->SetMaximum(signal);

ht->SetMinimum(-signal);

ht->SetStats(0);

ht->SetLineColor(2);

ht->GetXaxis()->SetTimeDisplay(1);

ht->GetYaxis()->SetNdivisions(520);

ht->Draw();

for (Int_t i=1;i<2300;i++) {

// Build a signal : noisy damped sine

Float_t noise = gRandom->Gaus(0,120);

if (i > 700)

noise += signal*sin((i-700.)*6.28/30)*exp((700.-i)/300.);

ht->SetBinContent(i,noise);

c1->Modified();

c1->Update();

gSystem->ProcessEvents();

//canvas can be edited during the loop

}

printf("Real Time = %8.3fs,Cpu Time = %8.3fsn",sw.RealTime(),

sw.CpuTime());

}When a class contains text or derives from a text class, it needs to be able to set text attributes like font type, size, and color. To do so, the class inherits from the TAttText class (a secondary inheritance), which defines text attributes. TLatex and TText inherit from TAttText.

Text alignment may be set by a method call. What is said here applies to all objects deriving from TAttText, and there are many. We will take an example that may be transposed to other types. Suppose “la” is a TLatex object. The alignment is set with:

The parameter align is a short describing the alignment:

align = 10*HorizontalAlign + VerticalAlign

For horizontal alignment, the following convention applies:

1 = left

2 = centered

3 = right

For vertical alignment, the following convention applies:

1 = bottom

2 = centered

3 = top

For example, align: 11 = left adjusted and bottom adjusted; 32 = right adjusted and vertically centered.

Use TAttText::SetTextAngle to set the text angle. The angle is the degrees of the horizontal.

Use TAttText::SetTextColor to set the text color. The color is the color index. The colors are described in “Color and Color Palettes”.

Use TAttText::SetTextFont to set the font. The parameter font is the font code, combining the font and precision: font = 10 * fontID + precision

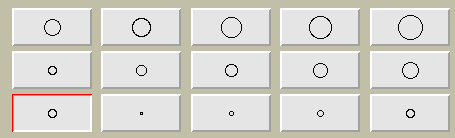

The table below lists the available fonts. The font IDs must be between 1 and 14. The precision can be:

Precision = 0 fast hardware fonts (steps in the size)

Precision = 1 scalable and rotate-able hardware fonts (see below)

Precision = 2 scalable and rotate-able hardware fonts

When precision 0 is used, only the original non-scaled system fonts are used. The fonts have a minimum (4) and maximum (37) size in pixels. These fonts are fast and are of good quality. Their size varies with large steps and they cannot be rotated. Precision 1 and 2 fonts have a different behavior depending if True Type Fonts (TTF) are used or not. If TTF are used, you always get very good quality scalable and rotate-able fonts. However, TTF are slow. Precision 1 and 2 fonts have a different behavior for PostScript in case of TLatex objects:

With precision 1, the PostScript text uses the old convention (see TPostScript) for some special characters to draw sub and superscripts or Greek text.

With precision 2, the “PostScript” special characters are drawn as such. To draw sub and superscripts it is highly recommended to use TLatex objects instead.

For example: font = 62 is the font with ID 6 and precision 2.

The available fonts are:

| Font ID | X11 | True Type name | Is italic | “boldness” |

| 1 | times-medium-i-normal | “Times New Roman” | Yes | 4 |

| 2 | times-bold-r-normal | “Times New Roman” | No | 7 |

| 3 | times-bold-i-normal | “Times New Roman” | Yes | 7 |

| 4 | helvetica-medium-r-norma l | “Arial” | No | 4 |

| 5 | helvetica-medium-o-norma l | “Arial” | Yes | 4 |

| 6 | helvetica-bold-r-normal | “Arial” | No | 7 |

| 7 | helvetica-bold-o-normal | “Arial” | Yes | 7 |

| 8 | courier-medium-r-normal | “Courier New” | No | 4 |

| 9 | courier-medium-o-normal | “Courier New” | Yes | 4 |

| 10 | courier-bold-r-normal | “Courier New” | No | 7 |

| 11 | courier-bold-o-normal | “Courier New” | Yes | 7 |

| 12 | symbol-medium-r-normal | “Symbol” | No | 6 |

| 13 | times-medium-r-normal | “Times New Roman” | No | 4 |

| 14 | “Wingdings” | No | 4 |

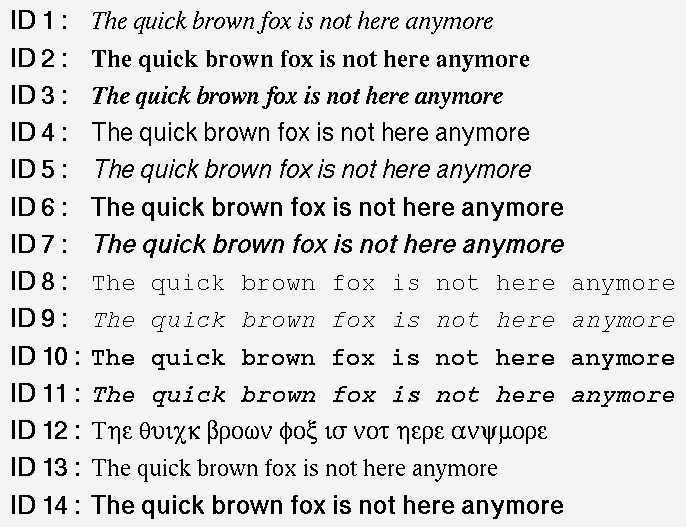

This script makes the image of the different fonts:

{

textc = new TCanvas("textc","Example of text",1);

for (int i=1;i<15;i++) {

cid = new char[8];

sprintf(cid,"ID %d :",i);

cid[7] = 0;

lid = new TLatex(0.1,1-(double)i/15,cid);

lid->SetTextFont(62);

lid->Draw();

l = new TLatex(.2,1-(double)i/15,

"The quick brown fox is not here anymore")

l->SetTextFont(i*10+2);

l->Draw();

}

}You can activate the True Type Fonts by adding the following line in your .rootrc file.

You can check that you indeed use the TTF in your Root session. When the TTF is active, you get the following message at the start of a session: “Free Type Engine v1.x used to render TrueType fonts.” You can also check with the command:

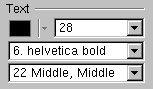

Use TAttText::SetTextSize to set the text size.

The size is the text size expressed in percentage of the current pad size.

The text size in pixels will be:

If current pad is horizontal, the size in pixels = textsize * canvas_height

If current pad is vertical, the size in pixels = textsize * canvas_width

The user interface for changing the text color, size, font and alignment looks like shown in this picture. It takes place in the editor frame anytime the selected object inherits the class

The user interface for changing the text color, size, font and alignment looks like shown in this picture. It takes place in the editor frame anytime the selected object inherits the class TAttText.

All classes manipulating lines have to deal with line attributes: color, style and width. This is done by using secondary inheritance of the class TAttLine. The line color may be set by a method call. What is said here applies to all objects deriving from TAttLine, and there are many (histograms, plots). We will take an example that may be transposed to other types. Suppose “li” is a TLine object. The line color is set with:

The argument color is a color number. The colors are described in “Color and Color Palettes”

The line style may be set by a method call. What is said here applies to all objects deriving from TAttLine, and there are many (histograms, plots). We will take an example that may be transposed to other types. Suppose “li” is a TLine object. The line style is set with:

The argument style is one of: 1=solid, 2=dash, 3=dot, 4=dash-dot.

The line width may be set by a method call. What is said here applies to all objects deriving from TAttLine, and there are many (histograms, plots). We will take an example that may be transposed to other types. Suppose “li” is a TLine object. The line width is set with:

The width is the width expressed in pixel units.

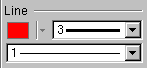

The user interface for changing the line color, line width and style looks like shown in this picture. It takes place in the editor frame anytime the selected object inherits the class

The user interface for changing the line color, line width and style looks like shown in this picture. It takes place in the editor frame anytime the selected object inherits the class TAttLine.

Almost all graphics classes have a fill area somewhere. These classes have to deal with fill attributes. This is done by using secondary inheritance of the class TAttFill. Fill color may be set by a method call. What is said here applies to all objects deriving from TAttFill, and there are many (histograms, plots). We will take an example that may be transposed to other types. Suppose “h” is a TH1F (1 dim histogram) object. The histogram fill color is set with:

The color is a color number. The colors are described in “Color and color palettes”

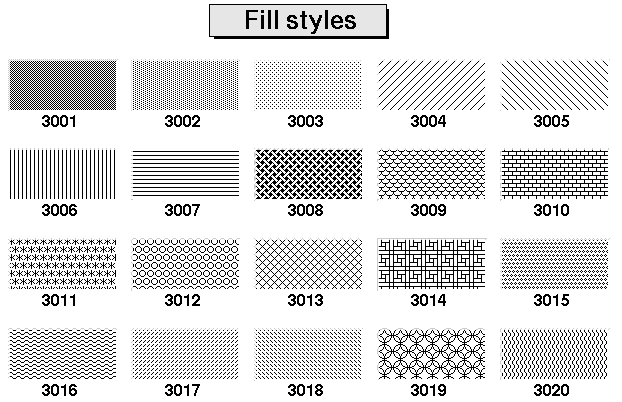

Fill style may be set by a method call. What is said here applies to all objects deriving from TAttFill, and there are many (histograms, plots). We will take an example that may be transposed to other types. Suppose “h” is a TH1F (1 dim histogram) object. The histogram fill style is set with:

The convention for style is: 0:hollow, 1001:solid, 2001:hatch style, 3000+pattern number:patterns, 4000 to 4100:transparency, 4000:fully transparent, 4100: fully opaque.

Fill styles >3100 and <3999 are hatches. They are defined according to the FillStyle=3ijk value as follows:

i(1-9) specifies the space between each hatch (1=minimum space, 9=maximum). The final spacing is set by SetHatchesSpacing() method and it is*GetHatchesSpacing().

j(0-9) specifies the angle between 0 and 90 degres as follows: 0=0, 1=10, 2=20, 3=30, 4=45, 5=not drawn, 6=60, 7=70, 8=80 and 9=90.

k(0-9) specifies the angle between 0 and 90 degres as follows: 0=180, 1=170, 2=160, 3=150, 4=135, 5=not drawn, 6=120, 7=110, 8=100 and 9=90.

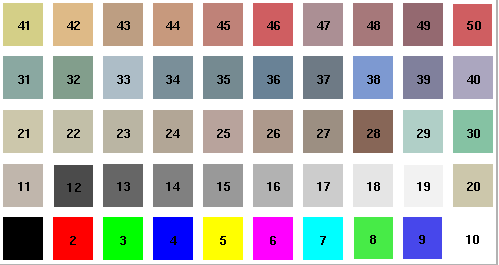

At initialization time, a table of basic colors is generated when the first Canvas constructor is called. This table is a linked list, which can be accessed from the gROOT object (see TROOT::GetListOfColors()). Each color has an index and when a basic color is defined, two “companion” colors are defined: the dark version and the bright version. Two static functions are available that return the bright or dark color number corresponding to a given color index. If these variants don’t already exist, they are created as needed:

Int_t dark = TColor::GetColorDark(color_index);

Int_t bright = TColor::GetColorBright(color_index);The dark and bright colors are used to give 3-D effects when drawing various boxes (see TWbox, TPave, TPaveText, TPaveLabel, etc). If you have a black and white copy of the manual, here are the basic colors and their indices.

The list of currently supported basic colors (here dark and bright colors are not shown) are shown. The color numbers specified in the basic palette, and the picture above, can be viewed by selecting the menu entry Colors in the View canvas menu. The user may define other colors. To do this, one has to build a new TColor:

One has to give the color number and the three Red, Green, Blue values, each being defined from 0 (min) to 1(max). An optional name may be given. When built, this color is automatically added to the existing list of colors. If the color number already exists, one has to extract it from the list and redefine the RGB values. This may be done for example with:

Where r, g and b go from 0 to 1 and index_color is the color number you wish to change.

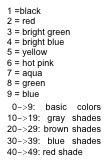

The user interface for changing the fill color and style looks like shown in this picture. It takes place in the editor frame anytime the selected object inherits the class

The user interface for changing the fill color and style looks like shown in this picture. It takes place in the editor frame anytime the selected object inherits the class TAttFill.

Defining one color at a time may be tedious. The histogram classes (see Draw Options) use the color palette. For example, TH1::Draw("col") draws a 2-D histogram with cells represented by a box filled with a color CI function of the cell content. If the cell content is N, the color CI used will be the color number in colors[N]. If the maximum cell content is >ncolors, all cell contents are scaled to ncolors. The current color palette does not have a class or global object of its own. It is defined in the current style as an array of color numbers. The current palette can be changed with:

By default, or if ncolors <= 0, a default palette (see above) of 50 colors is defined. The colors defined in this palette are good for coloring pads, labels, and other graphic objects. If ncolors > 0 and colors = 0, the default palette is used with a maximum of ncolors. If ncolors == 1 && colors == 0, then a pretty palette with a spectrum Violet->Red is created. It is recommended to use this pretty palette when drawing lego(s), surfaces or contours. For example, to set the current palette to the “pretty” one, do:

A more complete example is shown below. It illustrates the definition of a custom palette. You can adapt it to suit your needs. In case you use it for contour coloring, with the current color/contour algorithm, always define two more colors than the number of contours.

void palette() {

// Example of creating new colors (purples)

const Int_t colNum = 10; // and defining of a new palette

Int_t palette[colNum];

for (Int_t i=0; i<colNum; i++) {

// get the color and if it does not exist create it

if (! gROOT->GetColor(230+i) ){

TColor *color =

new TColor(230+i,1-(i/((colNum)*1.0)),0.3,0.5,"");

} else {

TColor *color = gROOT->GetColor(230+i);

color->SetRGB(1-(i/((colNum)*1.0)),0.3,0.5);

}

palette[i] = 230+i;

}

gStyle->SetPalette(colNum,palette);

TF2 *f2 = new TF2("f2","exp(-(x^2)-(y^2))",-3,3,-3,3);

// two contours less than the number of colors in palette

f2->SetContour(colNum-2);

f2->Draw("cont");

}Since ROOT 6.26, you can also define a palette based on an ASCII text file, using TColor::CreateColorTableFromFile("filename.txt") or gStyle->SetPalette("filename.txt"). The input file contains one color per line in “r g b” float format. This function is useful to profit from a full set of colour-vision deficiency friendly and perceptually uniform colour maps that are available to download

A new graphics editor took place in ROOT v4.0. The editor can be activated by selecting the Editor menu entry in the canvas View menu or one of the context menu entries for setting line, fill, marker or text attributes. The following object editors are available for the current ROOT version.

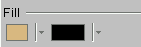

This user interface gives the possibility for changing the following axis attributes:

color of the selected axis, the axis’ title and labels;

the length of thick parameters and the possibility to set them on both axis sides (if +- is selected);

to set logarithmic or linear scale along the selected axis with a choice for optimized or more logarithmic labels;

primary, secondary and tertiary axis divisions can be set via the three number fields;

the axis title can be added or edited and the title’s color, position, offset, size and font can be set interactively;

the color, size, and offset of axis labels can be set similarly. In addition, there is a check box for no exponent choice, and another one for setting the same decimal part for all labels.

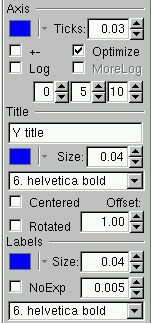

It provides the following user interface:

Fixed aspect ratio - can be set for pad resizing.

Edit - sets pad or canvas as editable.

Cross-hair - sets a cross hair on the pad.

TickX - set ticks along the X axis.

TickY - set ticks along the Y axis.

GridX - set a grid along the X axis.

GridY - set a grid along the Y axis.

The pad or canvas border size can be set if a sunken or a raised border mode is

selected; no border mode can be set too.

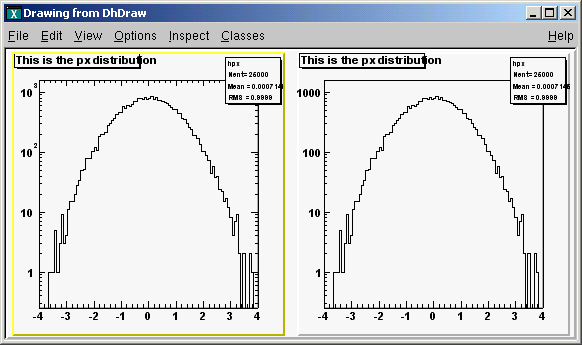

You can make a copy of a canvas using TCanvas::DrawClonePad. This method is unique to TCanvas. It clones the entire canvas to the active pad. There is a more general method TObject::DrawClone, which all objects descendent of TObject, specifically all graphic objects inherit. Below are two examples, one to show the use of DrawClonePad and the other to show the use of DrawClone.

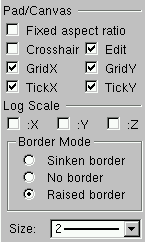

In this example we will copy an entire canvas to a new one with DrawClonePad. Run the script draw2dopt.C.

This creates a canvas with 2D histograms. To make a copy of the canvas follow the steps:

Right-click on it to bring up the context menu

Select DrawClonePad

This copies the entire canvas and all its sub-pads to a new canvas. The copied canvas is a deep clone, and all the objects on it are copies and independent of the original objects. For instance, change the fill on one of the original histograms, and the cloned histogram retains its attributes. DrawClonePad will copy the canvas to the active pad; the target does not have to be a canvas. It can also be a pad on a canvas.

If you want to copy and paste a graphic object from one canvas or pad to another canvas or pad, you can do so with DrawClone method inherited from TObject. All graphics objects inherit the TObject::DrawClone method. In this example, we create a new canvas with one histogram from each of the canvases from the script draw2dopt.C.

Start a new ROOT session and execute the script draw2dopt.C

Select a canvas displayed by the script, and create a new canvas c1 from the File menu.

Make sure that the target canvas (c1) is the active one by middle clicking on it. If you do this step right after step 2, c1 will be active.

Select the pad with the first histogram you want to copy and paste.

Right click on it to show the context menu, and select DrawClone.

Leave the option blank and hit OK.

Repeat these steps for one histogram on each of the canvases created by the script, until you have one pad from each type. If you wanted to put the same annotation on each of the sub pads in the new canvas, you could use DrawClone to do so. Here we added the date to each pad. The steps to this are:

Create the label in on of the pads with the graphics editor.

Middle-click on the target pad to make it the active pad

Use DrawClone method of the label to draw it in each of the other panels.

The option in the DrawClone method argument is the Draw option for a histogram or graph. A call to TH1::DrawClone can clone the histogram with a different draw option.

To copy and paste the four pads from the command line or in a script you would execute the following statements:

root[] .x tutorials/hist/draw2dopt.C

root[] auto p1 = surfopt->GetPad(1); // get the first pad

root[] auto p2 = lego->GetPad(2); // get the second pad

root[] auto p3 = contours->GetPad(3); // get the third pad

root[] auto p4 = c2h->GetPad(4); // get the forth pad

root[] TCanvas c1("c1","Copy Paste",200,200,800,600);